The Cross-Border Portability for Online Content Services Regulation forms a key action line of the European Union’s Digital Single Market initiative, and the EU Council of Ministers are looking to reach a consensus on the matter this month (May 2016). As it moves closer to a final draft, it is worth reflecting on some of the technical challenges the entertainment industry will have to grapple with in order to ensure compliance with the Portability requirements of the Regulation, which will apply to every provider of paid-for streaming (or downloadable) content in the EU from 2017.

As was highlighted in detail at the workshop on Location Spoofing Technologies we held with Olswang in London on 3rd March, the explosive growth in the consumption of media online (led by the likes of Netflix and iPlayer but now with hundreds of local OTT providers serving EU Member States) has led to a friction point between the demand for and ease of cross-border access to content, and the commercial model for such content that restricts its distribution on an exclusive basis to one broadcaster in one territory.

With the EU weighing in with their principles of a single European market for goods and services, the commercial model for the per-territory selling of content by the entertainment industry to broadcasters seems to be under more pressure than ever.

In our March 3rd workshop, we covered the major challenges around delivering technical solutions to turn the theories of the law-makers into practice. The key takeaways from that session (with some updates based on the latest draft Proposal for the Cross-Border Portability Regulation) were as follows:

LOCATION-BASED SERVICES TERMINOLOGY

As geolocation services are a relatively new topic to legislators (and still to some in the entertainment industry), it would be helpful to define what people mean when they use terms such as “geolocation” or “geo-fencing”. Distinguishing these two terms is important as they do not refer to the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably.

Geo-fencing refers to the placement of a virtual perimeter around an actual geographic area. In the case of EU Member States, this would mean erecting a digital border along participating country lines so only people within those counties would be able to benefit from the EU’s policies on cross-border access to online content. Geolocation on the other hand is the identification of the geographical location of an Internet connected device and/or its user. With regards to the EU’s proposal, geolocation would be used to determine the location of a user each time they attempted to watch content through their interactive devices.

HOW DOES GEOLOCATION WORK?

What is perhaps the most important thing to remember about geolocation is that it does not refer to any one particular type of technology. There are several different geolocation methods, each with its own particular strengths and weaknesses; therefore, there is no ‘right’ method of geolocation to use for all types of online streaming operations. Some may be better suited to locating users on a PC, while others are better for locating viewers via a mobile device, such as a smartphone or an iPad. The good news is that it is now exceptionally common for users to engage with geolocation technology on their devices, as they rely on mapping tools within those devices to get from Point A to Point B, to make sure that their taxi can find them, or that they have the correct information about which shop in their area has the inventory they require. Permissions for access to location information are asked for by the provider; the user normally provides permission in order to conduct the action required (i.e. find a gas station or get a pizza delivered). Location is checked only when the user interacts with that specific service, and the user can simply disable location checking anytime they do not wish to be tracked. For hundreds of millions of Europeans, that is the day-to-day normality of their experience of geolocation in the real world.

PRIVACY

Often the fear of an erosion of privacy has been used as an excuse to prevent the deployment of geolocation that actually works and is resistant to commonly available location spoofing tools (such as proxies and VPNs). However, this is a spurious fear since content streaming sites don’t ban the use of VPNs per se; instead they just don’t allow them to be used when somebody is streaming Copyright Protected material that is not authorized for a particular territory. Similarly, if a user consents to their location being checked by a native application such as BBC iPlayer or SKY Go, location is only checked (potentially to just a country level) when the content is streamed, and even that location tracking can be disabled by the user at any time. The user remains in control throughout the location verification process – a process which is considered absolutely normal and standard practice for the approx. 2 billion smartphone users around the world.

The need for location-based services to comply with data protection and privacy rules is already well-established under EU law. It seems an unnecessary and onerous burden on media streaming platforms to ban them from using location verification tools to ensure that their content is only being seen in the territories for which they have the rights to show it.

TECHNICAL ISSUES WITH THE EU’S PROPOSAL

The latest draft of the proposal in regard to Cross-Border Portability says that a service provider will be entitled to locate a viewer of online content SOLELY on the basis of IP geolocation. The issue with this apparent preference is multi-fold, not least that technology moves quickly and tying yourself (in legislation) to a closed list of acceptable geolocation methods is extremely unwise. Furthermore, while the reasoning for this choice may be more to do with the fact that IP geolocation is the ONLY method that the EU team are aware of, it could lead to a very restrictive and ineffective dead-end for the industries that will have to be reliant upon it for the foreseeable future.

BACKGROUND TO IP ADDRESS GEOLOCATION

Traditionally, the most common form of geolocation has been based around determining the location of an Internet user’s IP (Internet Protocol) address through databases containing known locations of assigned blocks of IP addresses. Although this method of geolocation has been around for almost as long as the internet and still has some valid benefits, it would seem wholly inappropriate if it was used by itself to deliver the needs set out as goals by the EU.

Firstly, IP geolocation as the sole method of geolocation for confirming all users’ physical locations for accessing content is simply a non-starter as it is not designed to provide location indicators for mobile data traffic – either as to the location of the device or the user [1]. As the EU’s 2016 Digital Scorecard has already correctly pointed out, mobile devices are now near ubiquitous (with several EU countries having more than one mobile subscription per capita now), so it seems somewhat flawed to use a geolocation method for mobile connected devices which has no ability to locate the user… at all [2]! The reason for this issue is that mobile connections (3G, 5G, etc.) share the same IP address of the ISP between all of their customers. So no matter where a UK roaming cell customer is in Europe, their IP (as far as the streaming platform is concerned) would always be coming from the UK!

Although IP has played a very useful role over the last 15 years and can still be helpful to a degree, IP geolocation was built for a time and a purpose that predates smartphones and the rise of mobile broadband. As such, if you were to choose one sole method for establishing location on the internet, it would seem problematic to select IP geolocation.

EASE OF FAKING IP GEOLOCATION

Another problem with IP address geolocation, even for landline internet connections, is that while IP is quite reliable in being tracked to a country level, the problem is that anybody who has the desire to fake their location can do so easily and cheaply (in many cases for free) [3].

According to recent research by Global Web Index, spoofing of location in order to access content that SHOULD be beyond reach thanks to IP geo-fencing is so common that as many as 50 million viewers of BBC iPlayer’s (theoretically UK only) viewers are actually coming from outside the UK. For Netflix the number is thought to be even higher – as many as 100 million [4].

These spoofing methods are now so prevalent that entire industries have proliferated around the world, enabling users to browse global catalogues of content that should be off-limits and inaccessible [5]. This causes havoc in the commercial engine of the creative industries, and undermines the pillars of the audio-visual industries in smaller countries where TV channels and domestic streaming sites cannot compete with international sites that surreptitiously enable international access to content that should be safely behind IP geo-fences.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, it is hard to see how a forward-looking policy, such as the EU’s Digital Single Market initiative, would shackle itself not only to just one method of geolocation, but a method that is clearly unable to deliver the requirements of the legislators today… let alone tomorrow!

What would seem eminently more effective is to follow best practice in the industry and:

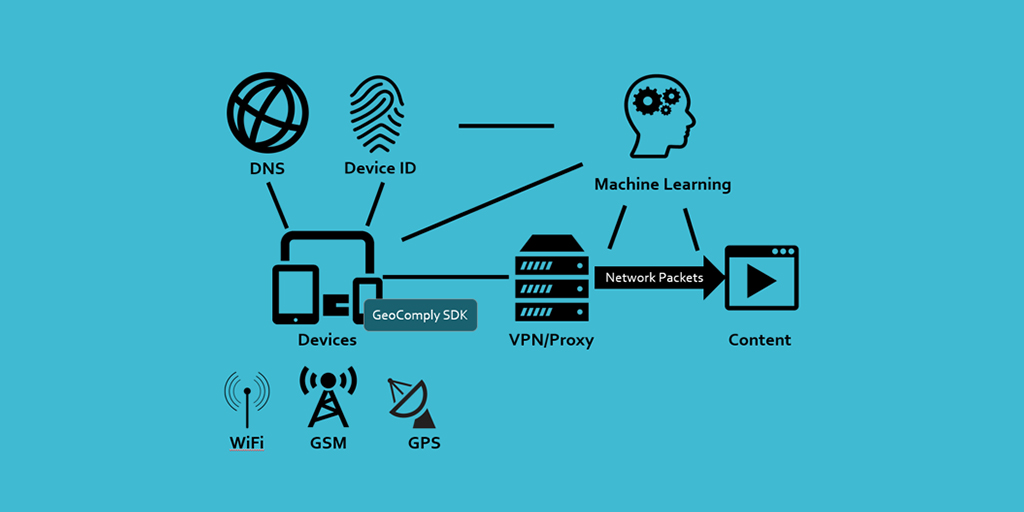

- Use the best, most reliable geolocation data available on each device at that time (Wi-Fi triangulation, Cell Tower Triangulation and/or GPS), and only use IP addresses if the connection is from a landline (rather than mobile); and

- Use sensible anti-spoofing tools to ensure that the location data has not been manipulated in order to access content that should be off-limits.

Certainly any geolocation method put in place by a streaming provider which is not fit for purpose (if it accepts IP geolocation data from mobile connections for example) or can be easily circumvented through commonly available spoofing methods (such as VPNs, DNS proxies, Mock Location settings on mobile devices, etc.) should not be considered acceptable under the EU’s framework.

The good news is that solutions exist today that do this very thing. In markets where location really matters to the provision of services online (and where token geo-fencing is not adequate) modern solutions are in place that ensure end-users’ compliance with location requirements, even in extremely high-traffic, mass market, consumer facing sites. If the EU really wish to achieve their goals they simply have to look across the Atlantic, where all of the tools they need are in use today across hundreds of millions of unique devices and customers – being located every day on conventional browsers and standard devices across the Windows/Mac/Android/iOS spectrum.

The easiest and most accessible example to use as a case study is the US Federal vs State jurisdictional challenge that online gaming has provoked in the United States. In the US, every state has autonomy over its gambling policies (to veto, or to offer some or all gambling products online). A state like New Jersey has licenses available for just about all forms of gambling, whereas Utah has an absolute prohibition. Yet this disparity in regulation between states is respected by technical solutions such as GeoComply’s, through sensible and highly effective geo-fencing of millions of users each day across consumer-facing sites (such as Betfair, Virgin, Pokerstars and Draft Kings) that need to ensure that their users actually comply with their Terms & Conditions as to their physical location – rather than just pay lip-service to the notion of location on the internet. What is common about all of them? They don’t accept IP as the sole form of geolocation, and they all use GeoComply’s Matrix for Best Available Location Data on the Device.

The world of technology has moved on since the beginning of the internet. It’s time for the EU’s understanding of what is possible on geolocation to move on too.

[1] Ingmar Poese, Steve Uhlig, Mohamed Ali Kaafar, Benoit Donnet, and Bama Gueye, “IP Geolocation Databases: Unreliable?,” ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review 41 (2011): 53, doi:10.1145/1971162.1971171.

[2] Mahesh Balakrishnan, Iqbal Mohomed, Venugopalan Ramasubramanian, “Where’s that Phone?: Geolocating IP Addresses on 3G Networks”, IMC 2009: Internet Measurement Conference, Chicago, IL, November 2009.

[3] “How To Hide Your IP Address?”, How Stuff Works, accessed July 27, 2012

[4] GWI Infographic: VPN Users

[5] The VPN Guru